Updated June 2025

In 2017 the Swallowtail and Birdwing Butterfly Trust (SBBT) voluntarily helped sustainable palm oil producer New Britain Palm Oil Ltd (NBPOL) and the Sime Darby Foundation (SDF), with the blessing of the Provincial Government of the Northern Province, Papua New Guinea (PNG), to develop a project that draws on authoritative research data in two books authored by SBBT trustees, “Queen Alexandra’s Birdwing: a Review and Conservation Proposals” (see Publications) and “Threatened Swallowtail Butterflies of the World: the IUCN Red Data Book”. An announcement about the project was made and there was widespread coverage in the press, including Down to Earth; PNG Today; The Ecologist; The Independent; Eastern Daily Press; BBC News Online; Daily Express; Daily Express. and Star2.com.

The initial three-year project, now financed by the SDF, has been operated solely by (NBPOL), which is a wholly owned subsidiary of what is now known as SD Guthrie Bhd and owns Higaturu Estate in the Popondetta region of PNG. NBPOL is a member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which requires its members to act as responsible stewards of threatened species on their properties. The intention is to enhance the seriously depleted wild population of this species with captive-bred specimens in a bespoke laboratory and flight cages in its own secure compound at Higaturu Estate (owned by NBPOL).

NBPOL with substantial assistance (4.85 million Kina, approximately £1.1 million) from the Sime Darby Foundation has now built and equipped a new laboratory, flight cages and foodplant nurseries within its secure residential and operations compound to try to breed Queen Alexandra’s birdwing, with a view to releasing it into areas that it once inhabited and that can be enriched with additional foodplants. The basic technologies for this have long been practised in PNG as demonstrated in this film (Pl. provide reference). Companies such as NBPOL have for many years been able to obtain previously deforested land for oil palm production but within their monoculture estates there still remains a residual complex of riverine and topographically dissected habitats that are difficult to access but have potential for conservation of butterfly communities.

By recruiting local, rather than expat project managers, these funds were made to last six rather than the originally estimated three years. Now that the SDF funding is at an end, SD Guthrie and NBPOL have undertaken to meet the annual running costs as part of their sustainability and conservation budget.

The SDF funding enabled recruitment of a professional entomologist Dr Darren Bito, a PNG citizen who obtained his doctorate at Griffith University, Australia. He was obliged to leave for personal reasons and was replaced by Dr Chris Dahl, also a PNG citizen.

The building of a new laboratory and a small flight cage was time-consuming due to the difficulty in locating competent building contractors in Popondetta, a region still accessible only by air and sea. The next problem facing the project was to persuade the males and females to mate, and it is for this reason that a larger (26′ high, 100’ long) flight cage was needed. Despite further delays caused by the COVID lockdown and, more recently, intertribal violence in the Popondetta area, the larger cage has now been completed and is being used. It has been named the Charles Dewhurst Flight Cage, to commemorate one of the project’s founders who died recently.

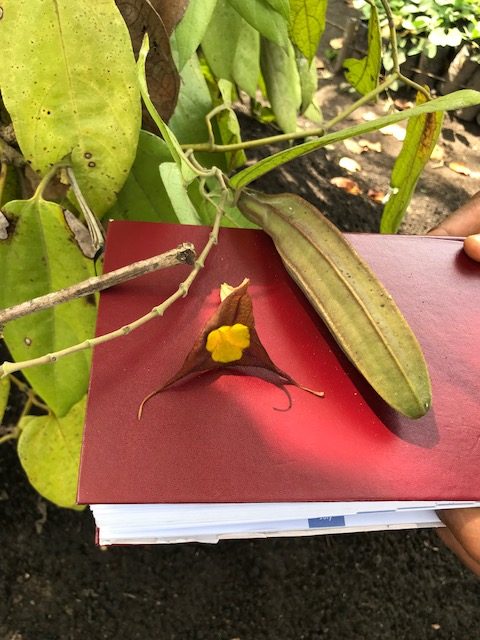

While waiting for work on the larger flight cage to be completed, efforts were made to perfect the technique of assisted mating on the much commoner Ornithoptera priamus and Troides oblongomaculatus, the former closely related to O. alexandrae.

We have had difficulty obtaining successful matings. Of the two which resulted in fertile eggs, in one case we bred a small number of adults to maturity, and currently have a second small batch in the process of pupating. Frustratingly other apparently successful matings have produced infertile eggs for reasons which are unclear.

There may be courtship problems relating to the prenuptial mating dance in which the male flies below and a little behind the female, occasionally overtaking the female from underneath and rising to the same level directly in front of the female. This appears to result in the tips of the female antennae brushing against or coming sufficiently close to scent the pheromones from androconial scales on the hindwing of the male. We believe that scales, or at least pheromones from the male hindwing may need to contact the female antennae to make her more receptive for mating purposes.

A further possibility, based on anecdotal information is that in order to facilitate successful mating, it is desirable that the male courting the female should previously have fed, or come in contact with the flowers of the Kwila tree (Intsia bijuga) which is not uncommon in the PNG rainforest. We have a specimen in our new flight cage.

We have also noted that adult males do not feed as readily in the flight cage as do females, and often therefore survive for a shorter period than females, despite offering nectar-bearing flowers and sugar solution higher in the flight cage and despite hand feeding.

There remain some fundamental questions that need to be addressed as the breeding programme gets into full swing. For example, we are aware that the lowland and semi-montane populations of O. alexandrae feed on different species of Aristolochia creeper. There are also problems of the levels of toxins in the leaves of foodplants apparently of the same species. It is possible that if the toxin level in the leaves becomes too high, perhaps as a result of higher temperatures or in reaction to earlier feeding by other larvae on the leaves, the larvae are poisoned and die. A full understanding of these complexities is therefore vital for successful breeding.

One problem which has been satisfactorily resolved, financed by an anonymous donation administered through SBBT was the comparative full genome analysis of the two now separate O.alexandrae populations, semi-montane and lowland. This was undertaken by Dr Fabien Condamine from CNRS, Montpellier, France, who visited Popondetta and successfully obtained genome samples. These studies have been written up by Fabien and his colleagues and have been published in Genome Biology and Evolution under the title ‘Genomics, population divergence and historical demography of the world’s largest and endangered butterfly, the Queen Alexandra’s birdwing.’ This study concludes that highland and lowland populations became separated about 10,000 years ago. It provides detailed DNA analysis of the 2 populations, advising against trying to crossbreed the two populations.

Also, before any releases can be contemplated, past surveys of existing populations need to be consolidated and possibly repeated so that a conservation baseline against which future success can be measured will be established.

The project is now in the process of building its advisory and management infrastructure with local and national government, local NGOs and community organisations. This short film introduces the issue. NBPOL has said it “… would like to place on record its appreciation for the assistance and general support which SBBT has provided to date with input on the planning of the project and assistance with publicity. Arrangements with the PNG authorities and NGO representatives are proceeding satisfactorily, as is the project itself. However, NBPOL greatly values the expertise provided in an advisory capacity by SBBT as well as their contributions over publicity. NBPOL looks forward to drawing further on SBBT’s advice and expertise as and when this is required.”

Additional information on Queen Alexandra’s birdwing is available from the conservation section of the SBBT website here, from Wikipedia, and from SPECIES+. An excellent BBC 4 Radio Programme by Mark Stratton gives an atmospheric sense of the butterfly in its natural habitat on the Managalas Plateau and may be enjoyed here. Worryingly, at an international level, evidence of continuing unsustainable deadstock trading practices in this species, however unbelievable, continues to be available through social media, as in the example below.

For further information see this useful article published in Der Spiegel and an announcement in 2017 of the newly listed 3,600 sq km Managalas Conservation Area, in the heartland of the butterfly’s habitat. The designation of this area, which has taken more than three decades to achieve, was supported by the Government of Norway and Rainforest Foundation Norway.

——————————————————————————————————————

There is an extensive paper written by Michael J Parsons in 1992 which discusses his many years of research on Queen Alexandra’s Birdwing in Papua New Guinea.