Britain is home to only one native species of Swallowtail – the iconic subspecies the British Swallowtail Papilio machaon britannicus. It is Britain’s largest butterfly and a symbol for its home region, the Norfolk Broads. Unfortunately, this has not protected the species from population decline and habitat restriction. Due to changes in habitat management and significant drying of vast areas of land to support agriculture, the wet, fenland habitat that the Swallowtail calls home has shrunk and become fragmented. Consequently, the butterfly’s range has contracted by over 55% in just 20 years.

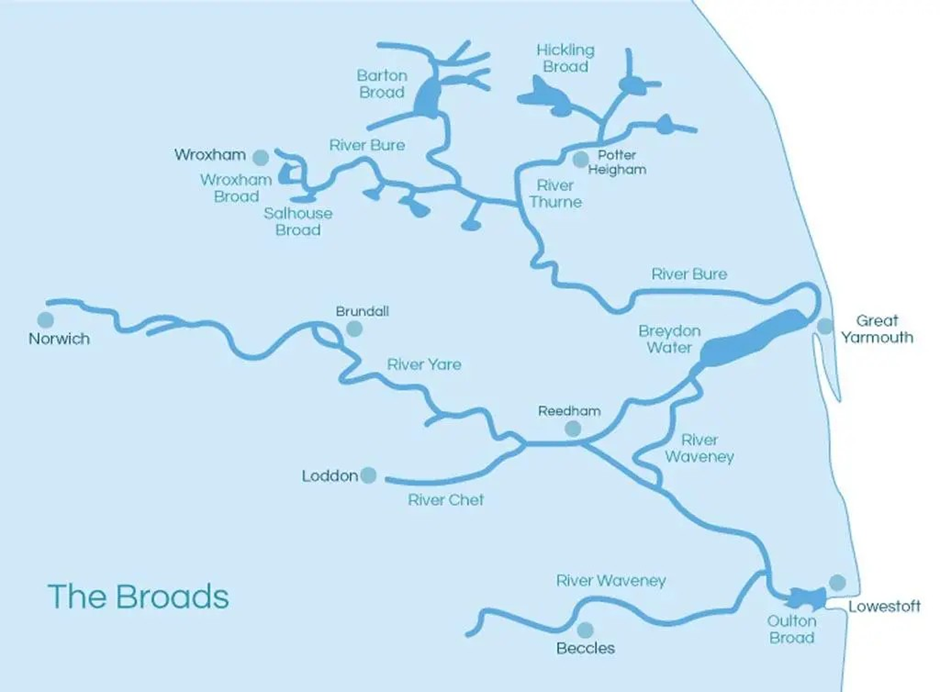

The Norfolk Broads, a manufactured network of rivers and lakes due to medieval peat digging, is Britain’s largest freshwater, wetland landscape. The resulting wetlands were created by water ingress from rising sea levels and have become a much loved, explored, and protected part of British culture. Climate change, however, is altering this special area. Where sea levels are continuing to rise and erratic weather patterns are causing seawater surges into the freshwater system on a more frequent and severe basis, the Swallowtail’s remaining stronghold is under threat. Its singular food plant, Milk Parsley Peucedanum palustre, cannot thrive in a saline environment and the combination of restricted breeding habitats and the very immediate threat to its larval food plant means the future for the British Swallowtail is precarious.

In an attempt to conserve the species, a PhD project is underway between Anglia Ruskin University, Jimmy’s Farm, and Nature’s SAFE in the UK. The project’s aim is to develop a method of cryopreservation for the fertilised eggs of the European Swallowtail P. m. gorganus, which is genetically similar to, but far more abundant than, the British Swallowtail. This will help us to safeguard against the rapid decline of the British Swallowtail’s current habitat and enable sufficient time to assess and trial other regions that may form a suitable new home within the UK.

The project is an exciting prospect and development in the world of insect conservation. There are currently no workable cryopreservation methods to conserve Lepidoptera in this way, despite years of use in humans and for many mammal species. It provides us with an opportunity to protect a nationally iconic species, whilst also developing innovative technologies for conservation. However, developing a cryopreservation method is not without its challenges and insect eggs can prove a tricky candidate.

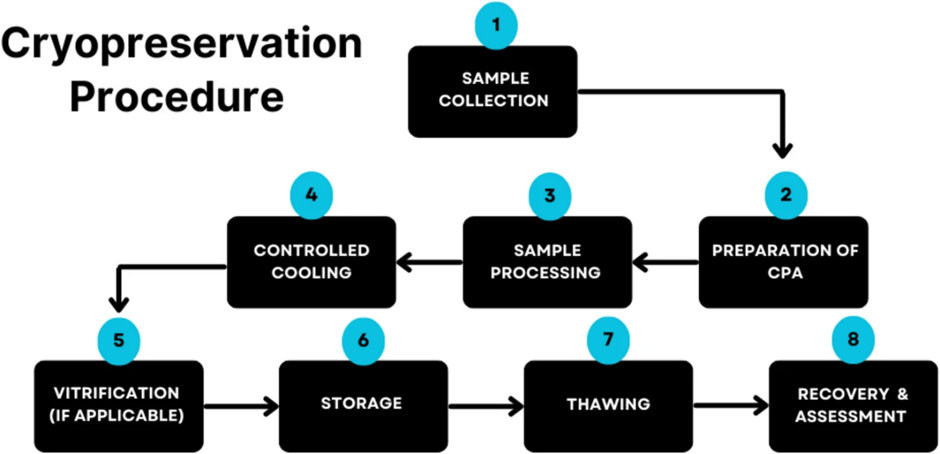

To successfully develop a method, several stages need to be achieved successively:

- Understand the egg’s full developmental cycle and timing,

- Remove the eggs external protective layer (the chorion),

- Load highly concentrated cryoprotective agents into the egg to dehydrate it,

- Vitrification via rapid cooling at extremely low temperatures (-196°C) with liquid nitrogen,

- The egg can then be stored in a frozen state until it is needed and can be rewarmed.

Rewarming can involve a wide range of techniques; from water baths to newer technologies such as nanoparticle-assisted heating and laser warming. We hope to trial newer technologies for rewarming as the more historic methods are not as likely to be successful for something as large and complex as the Swallowtail egg. Once the egg is successfully rewarmed, the egg should continue to develop as normal and hatch into a viable caterpillar. Their development will be compared to a non-frozen control group.

In a perfect world, at the end of the project we will have a reproducible cryopreservation technique with a high survivability rate. The technique can then be tested on the British Swallowtail to support its conservation strategy. But its development does not need to stop there. There is the potential to use the method across a range of Lepidoptera worldwide both for conservation and research purposes. Either way, it will be a busy three-years, with many questions, hopefully, both raised and answered along the way. Keep an eye out for future updates in Papilio! or via my LinkedIn.

Cassandra Barrett

PhD candidate at Anglia Ruskin University